Plan Les Watches: The watchmaking expertise behind Patek Philippe

If you know anything about the practical side of watchmaking, you will know that production is a sensitive subject. For example, you might see news about a massive new building being built by watchmaker A, and naturally wonder how many more watches will be made under that roof. If you know a little more about watchmaking, you will not be surprised to learn that more watches are not on the cards - at least not any time soon, and certainly not to the extent that production will suddenly double.

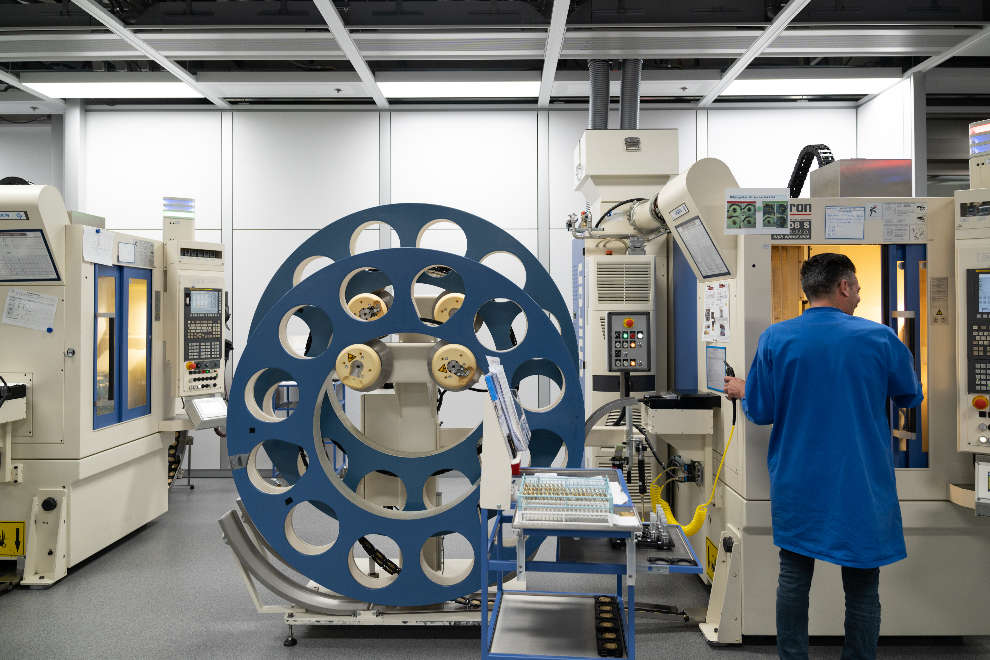

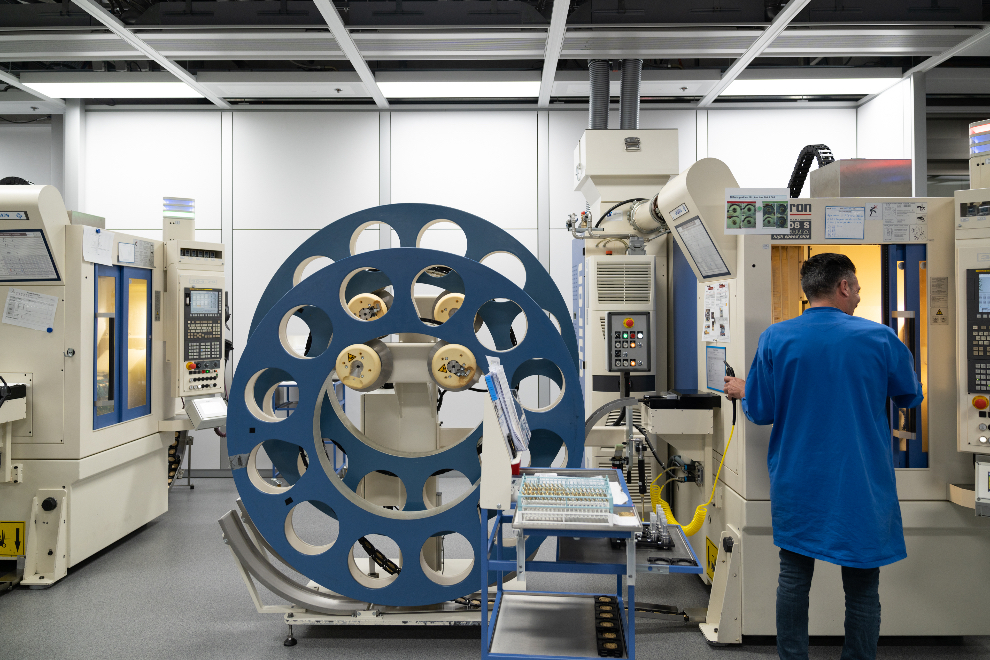

During a tour of Patek Philippe's new factory in Geneva's Plan-les-Ouates district (affectionately known as Plan-les-Watches or Plan-les-Watch), we were shown an astonishing number of CNC (computer numerical control) machines. It was literally a show-stopping moment for the press tour organised for Southeast Asian media, especially for those of us who understood that CNC machines can run 24/7. For a moment, this writer wondered how many brass movement blanks could be produced at the new PP6 facility with the multi-axis CNC machines. That silly moment passed quickly, however, as Patek Phlippe helpfully informed us that gears, pinions and arbours (also produced here on various CNC machines in a process called bar turning, where the raw material bars rotate but the tools are fixed) had to be finished by hand. Anything with teeth, really. To put it bluntly, this literally means that every spoke of every wheel receives individual attention, however minute.

Stepping back a little from this specific close-up, the reality of watchmaking is often surprising because these sites are often huge - the new facility we visited is 34m high, with 10 floors (four of which are underground, which Patek Philippe literally describes as subterranean, in good old secret hideout style), for a total of 133,650m2. Obviously, the site is huge, but Patek Philippe's production volume of 70,000 watches (this is the upper estimate; Patek Philippe does not disclose specific production figures) seems relatively small. What's needed here is an established scene, so let's take you back to 2019, in before-times - let's go back even further for a bit of context.

One of many movement blank or platine producing machines

In the beginning...

Ever since it was founded in 1839, and certainly since the Stern family took over in the 1930s, Patek Philippe has been on a mission to expand and improve its capabilities. In all this time, wealth has become more democratised and watches have found their way onto the wrists of more people than ever before. Bear this in mind when you visit the Patek Philippe salon in Geneva - one of three owned and operated by the brand itself - because this is where the watchmakers used to work. When the advent of quartz technology put an end to many a storied name and even sent the watchmaking trade into decline, those companies that soldiered on - Patek Philippe among them - found that they had to take steps to protect the entire industry. Indeed, the Patek Philippe Museum occupies a space once used by one of its suppliers, which has now become an in-house division - the famous bracelet maker Ateliers Reunis. While both the salon and the museum are impressive, they cannot compare with the most recent addition to Patek Philippe's production facilities.

When Thierry Stern took over as President of Patek Philippe, he was building on the work of his predecessor, his father Philippe. In 1996, the elder Stern had announced the construction of a factory in Plan-les-Ouates, which was completed by the time the younger Stern took over in 2009. To cut a long story short, Patek Philippe decided that it needed even more workspace, but it had to fit within the existing footprint of the site; the existing facilities, while modern, were simply not keeping pace with future needs. The solution unfolded in several stages, and work on the building known as PP6 (the subject of this story) began in earnest in 2015. Clearly, Thierry Stern wanted something big, and PP6 fits the bill. While this is a great story in itself, we are more interested in what might enlighten collectors and those still waiting for their chance to own a Patek Philippe watch.

Square plate with platine emerging from the aforementioned CNC machine; bevelling a balance bridge

Coming back to CNC machines and the shaping of parts with teeth, we can actually learn something interesting and perhaps specific to Patek Philippe. Not because it is the biggest and the best or anything like that, but simply because it is a rational way of working that the Geneva brand has adopted. The gist of it is this: the base plates produced here are not intended for complicated movements, but the toothed parts are shared by all the different calibres. Different machines are used to make plates and bridges for complicated watches. Why should this be so? The explanation given, and what we know ourselves, is that the components of complicated movements, including plates and bridges, are thicker than normal. They are filed to the appropriate dimensions (still thicker than standard movements) because the skilled hands of a craftsman can handle more complex and delicate operations than even CNC machines can.

Crafted by hand

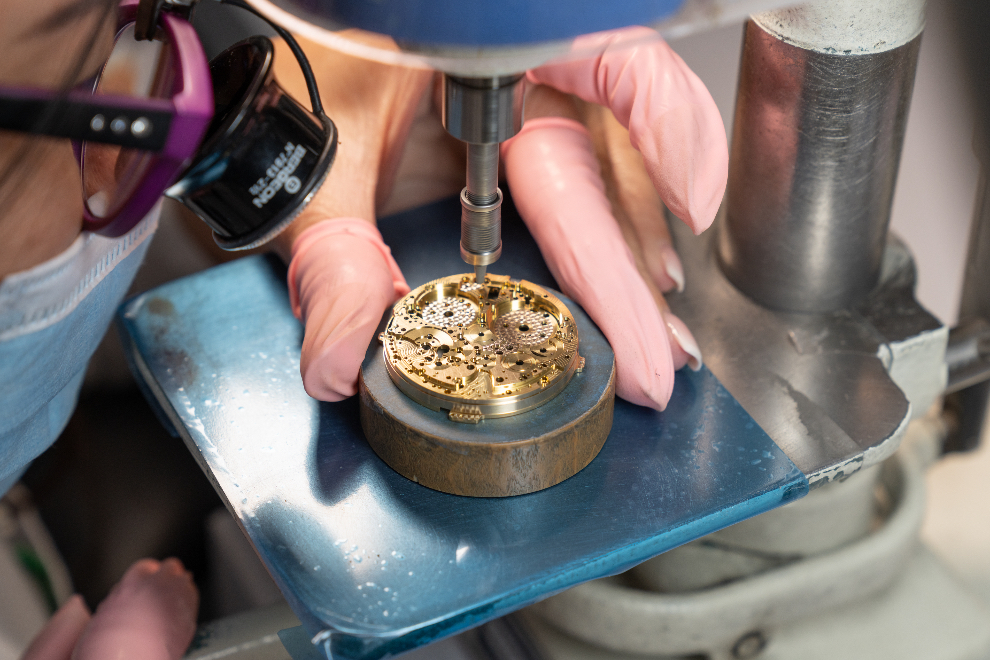

The tourbillon bridge is a good and often used example, as the rough part is worked on intensively by hand. Extra material is also used to compensate for the inevitable small imperfections. Gears and pinions, on the other hand, can be made to a standard specification. Not that any brand discusses things like errors, but they do happen, because if you take too much off when chamfering, for example, there is no going back; this writer knows that from experience, as the tolerances here are beyond what the naked eye can detect. Suffice it to say that if you are looking for reasons why Patek Philippe might be limited in production - even with automated processes in the mix - you will find an important point in the hobbing process and what follows. Hobbing is the technical term for making teeth on parts.

Circular graining being applied to the base plate of the Grand Master Chime calibre.

Unfortunately, space restrictions are just as much a part of us as they are of a watchmaker like Patek Philippe, so we have to move on to bracelets and metiers d'art. We would have liked to tell you more about movement assembly, but this was not possible on this occasion, and this operation actually takes place in another building here at the Plan-les-Ouates factory. In this context, we would be remiss not to mention Patek Philippe's Advanced Research department, located on the third floor of PP6. Unfortunately, it was not part of the tour this time, but we hope it will be in the future. Having a reason to return to the Patek Philippe factory is no reason to complain.

And so we move on to the bracelets, which will be popular with the wider world of watch enthusiasts. Of course, the bracelets we saw in production were for the Nautilus, which is perhaps the most exclusive and famous bracelet in the world - the GOATs of bracelets, you might say. It is always amazing to see a bracelet take shape, link by link, although it must be said that the raw material here arrives in the form of a bar in the required rough dimensions (complete with a groove in the middle). Famously, there are 55 steps involved in making the Nautilus bracelet, and Patek Philippe has taken its time. Now, you might wonder why all the fuss about bracelets, but of all the manufacturers we visited this year, Patek Philippe is the only one to show the world how it makes its bracelets in its own factory. In fact, most watch brands outsource their bracelet production to a specialist, but Patek Philippe acquired its own supplier many years ago (as briefly mentioned above).

Case Study

To continue with the making of bracelets, the shaped bars are sent into the bar-fed machining centre to form individual links. This is a milling process, to keep things succinct, and involves many quality-control steps as well as hand-correction, but these are not part of the 55 steps. As you know, there are two main parts to the bracelet links – the H-shaped bit and the centre link – and these are individually worked before being assembled (with pins). Even after being assembled, there is still buffing and chamfering to be done, and the centre links are actually polished further to achieve the signature mirror polishing. This is done by protecting the H-links with perforated masking tape and polishing the length of the assembled bracelet.

Moving on to case-making, we have just about enough space to get into another famous Patek Philippe signature, the hobnail case- middle decoration (which also appears on bezels sometimes). This is a Clous de Paris guilloche technique done with a hand operated comb and plane lathe. You will have to imagine the technique required to maintain the right amount of pressure here (the part moves while the lathe remains still). On the making of the cases themselves, this is pretty straight-forward, with bar-turning (just as movement components are made), milling, stamping and polishing in the mix. We note for the record that Patek Philippe is also amongst the few watchmaking firms that produce their own cases, and have invested heavily to bring this know-how in-house.

Finally, we will save the last word for Rare Handcrafts, even if it means that we have to leave the complications at this point prematurely, leaving just a word or two for gem-setting in the captions. Our tour included a demonstration of champlevé enamelling, just one of the 12 techniques in which all Patek Philippe enamellers are proficient. Champlevé involves painting within the lines, which are essentially cavities carved into a dial, and this technique is particularly suitable for enthusiasts to have a go at, as you can see here.

A demonstration of all the techniques would either be cursory or take days (if you visited the Grand Exhibition [in Tokyo or Singapore in 2019], this part of the tour is a bit like that segment), and one must bear in mind that Patek Philippe also has other artisans working on dials at the specialist dialmaker Cadrans Fluckiger in St. Imier. It also employs external specialists such as Anita Porchet, whom some of you will have met or seen in action in Singapore, while other craftsmen work from home on their own machines.

In this sense, the Patek Philippe Manufacture is a kind of home for watches, where they are lovingly prepared to be sent out into the world. Remember this the next time you look at your own Patek Philippe, because someone at home in Geneva is trying to imagine the immense pleasure you will take in it. If a Patek Philippe is still on your horizon, we hope that this story will help convince you that it is worth taking a step towards that imaginary line.

This article first appeared on WOW’s Legacy 2024 issue